Please read the two excellent histories of the Walker House, a snapshot history by Mineral Point resident Nancy Pfotenhauer and a 2,000-word history by Cincinnati resident and Loyola University Chicago history major Chris Benson. A few words should be added about the Benson essay to warn readers that it is a preliminary attempt and an incomplete one, ending in the early 1950s. Benson came to the Walker House in May 2012 with two goals in mind: to collect as much information as possible about the Walker House from local newspaper morgues, court records, official archives, and oral histories; and to begin organizing the material into an unofficial history of the House. He left behind on Memorial Day weekend dozens of sources and the history below, both of them as invitations for another historian to correct inaccuracies, flesh out contexts and anecdotes, and produce an official history of the Walker House.

The Walker House

by Nancy Pfotenhauer

Pfotenhauer, Nancy. A Field Guide to Mineral Point: The Buildings, Past and Present, of a Historic Wisconsin Town. Mineral Point, WI: Little Creek Press, 2012.

The Walker House

by Chris Benson

William Walker was an Irishman born on January 1, 1814. Whether driven away by the recent Tithe Wars, British oppression in general, or mere hope for a better life, in 1839 he left his homeland from the port city of Derry and arrived on September 4 of the same year in Maine. After spending two years at Joliet, Illinois, he settled at his final home, Mineral Point, in Iowa County of what was then the Wisconsin Territory.

The discovery of lead ore (also called galena or mineral) in 1828 started Mineral Point’s settlement and prompted a rapid increase in the area’s population, so that there were 4,000 non-native people in Iowa County by 1840. Unmarred by the drifting of glaciers during the last Ice Age, Southwest Wisconsin has topography similar to Walker’s homeland. On July 4, 1836 Henry Dodge was sworn in as governor of the newly created Wisconsin Territory in Mineral Point.

The first five years of Walker’s life in Mineral Point are mostly mystery. Because he does not appear on the tax rolls until 1846, he may have lived with another family in the town. He worked as a teamster before he could open his own business. As a teamster he often made the eight day trip to Galena and back, hauling lead ore to Galena and returning with various goods. He may have attended the hanging of William Caffee, where the crowds were reported as large as five or six thousand. William Caffee was a hot-headed youth originally from Kentucky, and on February 22, 1842, shot Samuel Southwick at a party in Gratiot. Caffee was enraged when he was skipped for dancing, a rare opportunity in a frontier territory where the population was predominantly male. He took the dancing list, and when he agreed to step outside and talk out the issue, a crowd, some wielding sticks, chased after him. Caffee, not used to being challenged on his big talk, was frightened. When the crowd continued to advance despite his protests, he panicked and shot the most belligerent member, Southwick. His threats were twisted as evidence for premeditated murder, and he was condemned to death. On November 1 Caffee was hanged from makeshift gallows in Mineral Point, and most people of the County, and many surrounding counties, decided to make a picnic of it. Whether or not at the hanging, Walker during 1842 courted Latitia Gibson, whom he married July 23 and whose family he may have been staying with in town.

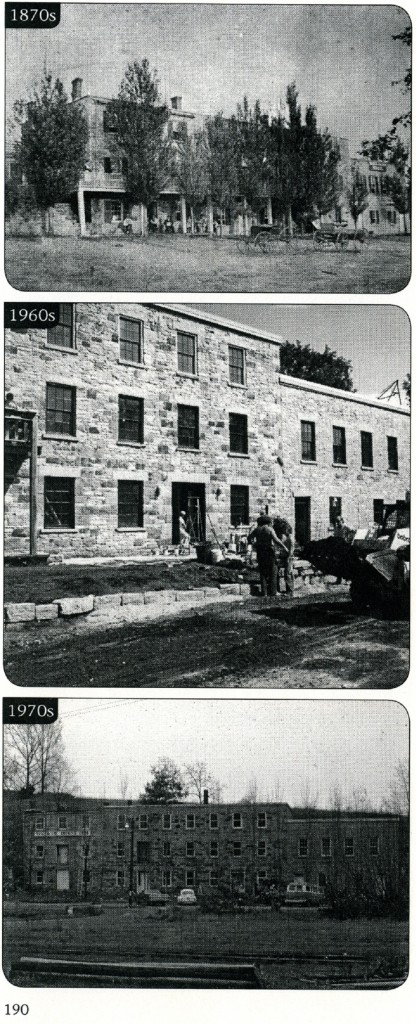

By 1846 Walker was established in Mineral Point. He purchased some property in the area, and established his business as a teamster and later as a lime manufacturer. In 1845 Walker had purchased two large lots to the southeast of town, and by 1848 had begun building on them. This first building was soon identified as his home. Walker endured the mass exodus from Mineral Point during the California Gold Rush, though his property lost much of its value. Over the next few years he focused on his business in the city, but he saw a valuable opportunity in the arrival of the railroad in 1857. The railroad tracks ran next to his property in the southeast of town, and the depot was but a stone’s throw from his home there. He rapidly began developing his property. In 1857 he constructed and began renting out a tavern there, and by 1859 had added a boarding house, which he also rented out. The Mineral Point Tribune announced on June 4, 1862, that Walker had opened a stone hotel on the premises, and because none of the earlier buildings were nearly old enough to warrant destruction, it was certainly either one or a combination of them transformed for the purpose of “accommodating the Traveling Public.” The Mineral Point Hotel was so close to the railroad depot that many pictures of locomotives there cannot help but at least include the sign from the building.

In 1866 an addition Walker made to his hotel established it as the largest in the southwest portion of the State of Wisconsin. The building rented 16 rooms, with a washbasin in each, and outhouses at either end. “Good Stabling and a cattle Yard attached to the premises” allowed Walker to accommodate travelers on horseback and stagecoach as well as those from the railroad. Despite a robbery that occurred there in December of that year, the hotel maintained a good reputation. Newspapers from the time praised Walker as a man who “knows how to manage an institution” and as an “enterprising proprietor.” The journalists reflecting on the year 1866 remarked on the hotel’s addition as a great accomplishment, all the more important as Mineral Point fell from grace in other ways. The town had rapidly become less important, with population decreasing from 2,900 in 1847 to 2,400 1860, and the county seat moving from Mineral Point to Dodgeville. Throughout the rest of his life William Walker successfully managed the Walker House as a hotel though also taking on longer term boarders. He even made further additions, the last being the north section, which had only one story in 1872, and by 1881 had invested approximately $10,000 into the building. He was one of the wealthiest men in Mineral Point by the 1870 census. At the same time the increased mining of zinc and the establishment of the zinc plant slightly south of the city established his part of town as industrial, and Walker and his hotel benefited from this development.

The Walkers had one child, William, but he had died by 1881. By 1899, Latitia Walker had also perished, and William Walker was cared for by his niece, Miss Sara Eskine of Monaghan, Ireland. Eskine had been living in the Mineral Point Hotel for several years caring for the elderly Walkers, and when William Walker died in May, 1899, he left her everything, including eleven thousand dollars and the hotel, now identified as the Walker House. By January 1900, however, Eskine was receiving special medical treatment in Battle Creek, Michigan. While she seemed to be recovering, on February 3 her heart stopped, and telegrams were sent to Mineral Point for the retrieval of the body. Two men answered, J. U. Oates and Charles Curtis.

Charles Curtis was a stonemason from Newland East, Cornwall. His father had been a stonemason, and Curtis was said to have taken up the trade at the age of 12. He immigrated to the United States around 1888, and he lived briefly in northern Wisconsin and Dodgeville before settling at Mineral Point in 1892. In the 1900 census he was listed as widowed, but later in that year he married his second and last wife, Kathryn Jane Ivey. A few months before Sara Eskine died she sold the Walker House to him for $3,000. Curtis was not as much of a businessman as Walker, but even so he converted the Walker House from a hotel to an apartment building upon purchasing it and ran a successful business there. Curtis did not care so much for money, and was more artist than entrepreneur. For fourteen years he worked as a stonemason at Taliesin for Frank Lloyd Wright, who praised him as “kind and tolerant” and as an artist who produced stone walls “as fine…as the finest in the world”. When an elderly artist, convinced of his uselessness due to old age, visited Taliesin, Wright introduced him to then eighty-one year old Curtis. The example of Curtis is proof against many myths linking old age with weakness or uselessness believed then as well as today. At Taliesin Curtis worked mainly for the love of his art and asked for only modest pay. He worked there, he said, because “I believe it’s a grand idea.” He was further lauded by Abe Dombar, who worked with Curtis at Taliesin. Dombar described Curtis as “an artist and a philosopher”. Curtis often let out poetic exclamations such as “hain’t she the berries?” and said “h’I like to get the feel of the rocks into me ‘ands.” Curtis was a master of stonemasonry who loved his craft. Even after retiring from Taliesin (Wright owed him $1,700, though Curtis insisted, “Mr. Wright was good to me”), he worked for a year and a half restoring some of the buildings on Shake Rag in the Pendarvis district with Bob Neal and Edgar Hellum. Outside of his work, Curtis was also admired by townsmen for his compassion and simple honor. Asked if he’d do a wrong if no one would ever know, he responded “H’I’ll know it’s there and h’I don’t want to be on bad terms with myself.” He told Wright he didn’t know how to not be happy. He rose eagerly in the early morning and loved eating, working, and companionship. Here was a man who was an artist in life as well as in stone.

The artistry of Curtis was well matched in the artistry of the Walker House, his home and major source of income. There are no records of Curtis making any additions to the property, but the man and his home are different examples of the same philosophy. Described as a “simple utilitarian building”, the Walker House is adorned with smooth stone lintels contrasting with irregular, roughly cut limestone and sandstone. Any stone of decent size was eligible for the facade. Vernacular in architecture and native in material, the building could be compared to Curtis’ native Welsh accent. Like Curtis, the building is not beautiful because of ostentation or flamboyance, but because of simple quality and honest confidence. The two are not pretty—they are glorious. Similarly, both the structure and the man bravely resisted the onslaught of age, but in this, of course, Curtis failed.

After 89 years of hard labor, simple living, and incessant smoking, Charles Curtis passed away on January 15, 1943. The journalist announcing his death sadly recalls his iconic greeting, “Hello, how is the boy,” and praised Curtis’s life as “long and useful”. Not needing to invent any virtues for the master workman, the obituary was mostly a republished article by Abe Dombar, and occupied the most prominent position on the front page of the Mineral Point Tribune. Curtis was succeeded by his wife as well as a few nieces and nephews, but had no children of his own. Relatives from Cornwall, hearing about the worth of the Walker House property, inquired about their place in Curtis’ will, swearing deathbed promises were made to their father. Their efforts were to no avail. The Walker House passed from Curtis to his wife, Kathryn. Kathryn in turn made her half-sister, Nellie Ivey, co-owner.

The death of Charles Curtis was by no means the death of art in the Mineral Point community. In 1939 Max and Ava Fernekes arrived, the first of many artists that would choose Mineral Point as their home. As lead and even zinc mining continued to diminish in the first quarter of the twentieth century, Mineral Point was forced to redefine itself from a mining town.

Nellie Ivey and, before she died in May 1946, her half sister Kathryn Curtis, did not take as much care of the Walker House as Charles Curtis or William Walker had. In the late 1940s this building became a lower-class and even semi-abandoned apartment building holding six or seven families. Tramps resided on the first floor of the building. Newlyweds sometimes lived there before buying their own home, but this does not mean the Walker House was bathed in love. It is around this time that a baby is said to have been abandoned in a Walker House outhouse. (The manuscript breaks off at this point.)

Rausch, Joan and Carol Cartwright. City of Mineral Point, Wisconsin Intensive Survey Report. Architectural Researches Inc. La Crosse, Wisconsin. 1992.